(With winter still firmly in charge in my part of the country, motorcycle travel is limited to day trips. Here’s an account of a longer trip in 2008. By John G. Rice of the Bluegrass Beemers Club)

For years, my brother-in-law Jay Smythe and I had contemplated another western bike trip. After many false starts, thwarted by the Army’s need for Jay to be somewhere else, like Iraq for example, we finally seized our opportunity. I flew out from Kentucky to Washington and on a late summer Sunday morning, Jay on his 1993 BMW R100R Mystic led me, riding his 1983 BMW R100RT out of his temporary home in DuPont, Washington, down through Ft. Lewis where he was stationed.

The fort is a beautiful place, every blade of grass manicured to perfection and all the buildings well maintained. Amazing what one can do with nearly unlimited manpower, most of which has little to say about the tasks to which they are assigned. It is a tranquil setting for young people to learn to do the horrible necessary things that defense requires. Jay took us down some back roads through the woods on post, past many dirt roads that would be tempting on different machines. Finally, we made it to a state highway that wound down through what we in Kentucky would call mountains, but here are just foothills. It was cold and a bit foggy here and there, at 7:30 in the morning and we kept a close watch out for animals making their morning forays. I was unfamiliar with the RT and was having a hard time keeping up with Jay as he made his usual smooth arcs through the curves ahead.

We stopped for a warm-up and to purchase a map at a convenience store about an hour down the road. There we met a rider on an R1150 GS, carrying camping gear and festooned with the electronica that seems to naturally grow from the handlebars of such bikes… His name was Dave and he was in the middle of a month out on the road, having sold a business in April and thus having both time and money on his hands. We left him there and went on our way down to Highway 12, one of the few east/west connectors in this part of Washington, headed for the Canyon Road near Yakima, which we had taken north to south on another trip and now would do the other way. It’s too good not to do again.

In the little town of Ellensburg, we stopped for gas and again ran into Dave, who asked if he could accompany us for a while. I guess there is for some such a thing as too much solitude. We agreed and the three of us headed up into Yakima Canyon. This road is one not to be missed if ever the occasion arises. It winds along the edge of the canyon, with the Yakima river down below and the ever-rising brown hills on either side. The curves are, like many roads out here, perfect for motorcycling., wide open sweepers easy to see through, with pavement just rippled enough to keep it interesting. On this Sunday in August the river held numerous kayaks, rafts and in places, whole parties of people standing in the shallows drinking beer from floating coolers. At the top of the canyon, we resisted the urge to turn around and do it again, opting instead to keep going toward our goal of Glacier National Park.

Up on the high desert country, a harvest has been going on. Square bales of hay, each the size of a large refrigerator are piled into house-sized masses looking as solidly fitted together as the Pyramids. The fields go on forever, cut stubble the height of a man’s ankle, the color of the crust of the best apple pie you ever ate, as far as one can see and over the horizon from there. The clipped rows are so straight and long, going out of sight, that one wonders if the tractor driver still remembered how to turn the beast when he got to the end.

We stopped briefly in the town of Colton, where we contemplated staying and Dave went on. Before going, he gave me a lesson in the map functions available on the Iphone he was carrying on a handlebar mount. I had one, the older version, but had no idea of such features, being basically a Luddite with tools beyond my comprehension (think of the protohuman in “2001, A Space Odyssey” who picks up the jawbone….he knows what he has in his hand is important, just not yet why). His lessons were to prove quite handy later in the trip.

Jay and I failed to find any accommodations that met even our minimal standards, so pressed on up the forest road toward the border. At the town of Ione, we found a small motel, “rustic” in its features, and there again met up with Dave. The motel clerk told us that the only restaurant in the area closed in 20 minutes, so we mounted up and rode there with gear still on our bikes. As we walked into the Cabin Grill, the waitress turned over the “Closed” sign to face outside. Dinner there was surprisingly good, perhaps the more so because we almost didn’t get it.

Jay at the Cabin Grill

Back at the motel, the three of us sat out on a picnic table beside the lake with the proprietor, swapping travel stories and listening to the owner regale us with lists of the animals he’d killed in the area. The next morning Jay and I were ready to go at daylight but there was no sign of life from Dave’s room, so we headed out on our own again.

The road down to the only border crossing followed a lakefront, winding in and out of the shoreline. The sun was to our right, coming through the trees like a strobe light making the curves somewhat surreal. At the town of Newport, we found ourselves in Idaho with no formal announcement that the border had been crossed. Breakfast was at the Riverfront Café, oddly enough right on the river, where we learned all about the robbery at the restaurant (“an inside job!”) the waitresses’ impending retirement and her plans for The Big Trip in her camper.

We rode on down route 2 to Sandy Point and picked up 200 south around Lake Pend Oreille into the mountains, then back north on 56 for spectacular views of mountains and lakes and forest. The pine forest came back, though not entirely successfully, with brown hills peeking through.

Leaving Newport, we followed Route 2 along the Priest River and a lake down into a low valley. As we neared Montana, the valley opened up into the wide grassy bottom, hemmed in by tall mountains that we’ve all seen in the movies. There should have been a wagon train on the trail, with a tall, square-jawed hero in the saddle of a great brown horse, out in front leading the way. Instead, there were campers and pickups and the occasional motorcycle, going about the rather ordinary business of we modern humans.

Since our bike trip motto is “we ride for pie” we made our first pie stop of the day in Libby Montana, where I also wanted to buy another layer for warmth. Being August, I hadn’t given enough thought to the temperature changes that come with altitude and latitude. We found the imaginatively named Libby Café with a pie case well stocked and a helpful young waitress who told us she had moved there from North Carolina. “I didn’t realize that what we had down there weren’t really mountains until I moved here” she said. A selection of pie slices became our lunch, including Hackleberry, a local delicacy which must be picked wild and reportedly cannot be cultivated.

Also of note in Libby, a business with a large sign advertising its two specialties: “Gifts” and “Irrigation” I was trying to think of the last time I considered giving someone an irrigation system for that special occasion, and if one would, how should it be wrapped?

We made our way up through Kalispell, a name that just seems to have some true western cache about it, to Whitefish where we found a room for the night. Our hotel, the Downtowner, had seen better days a long time ago, but met our requirements of being relatively clean, quite cheap and within walking distance of a restaurant with beer.

Our first stop for the evening was the Great Northern Brewery where we sat at the second-floor bar looking out of the glass front over the main street. We tried a flight of samples, each finding some we liked (usually not the same ones, though the Frog Hop Pale Ale was a winner) and definitely agreeing on one neither of us found appealing. For my admittedly non-universal taste, the Pack String Porter was the best on offer. (When asked about the significance of the name, the bartender said “They just made it up”). Thus fortified, we wandered on down the street finally settling on “Lattitude 48″, an eclectic little restaurant with a varied menu. The food was excellent and they also had a decent beer and wine selection. We were sufficiently sated such that even I couldn’t go for dessert.

Back at the motel, we met up with a group of a half dozen or so Harleys and their riders just checking in. They had Illinois plates, but apparently had trucked the bikes to somewhere nearer the west and were riding from there. We talked to some of them about their machines and their travels, and realized later that none of them had expressed any interest in the two old Beemers or where we might be going.

The next morning, Tuesday, we headed out at first light for Glacier National Park, stopping in the town of West Glacier, the gateway to the park, for breakfast. A couple pulled in, each on a motorcycle, with the man of the pair wearing a ventilated jacket. Jay and I looked at the various multiple layers we had on and concluded that either we have become wimps, or he was just a mutant impervious to cold. Still no definitive answer to that question.

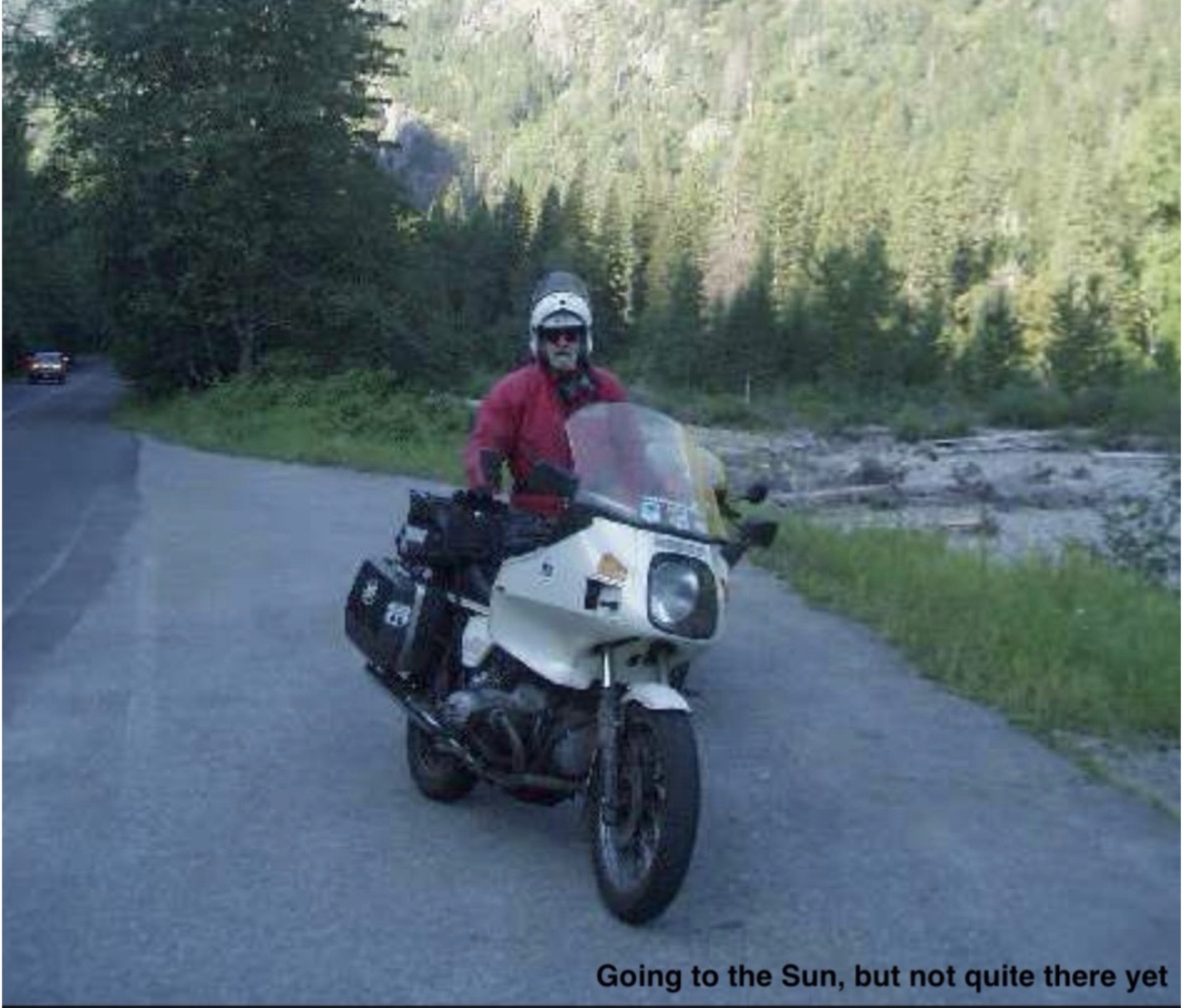

Into the park, paying heed to all of the signs warning us not to feed, or become food for, the bears, and then onto the “Going to the Sun” road. I had heard about this road all my adult life and was expecting something remarkable. For the first several miles, it was pretty, following the glacial lakes and the stream, high mountains in front of us lit by the rising sun, but it was just a pretty mountain road.

Then it began to climb. And climb. And climb some more. We ran into several spots of construction where the pavement had been stripped down to bare earth and the traffic stop delays gave us a chance to get off the bikes and look around. The road is cut, literally, into the side of the mountains like a goat track circling a hillside. There is a low rock wall, not really enough to keep a car from going over and nothing that would offer much impediment to a bike headed off the edge. And if one did so, the rider would have a lot of time to think about it before hitting anything on the way down.

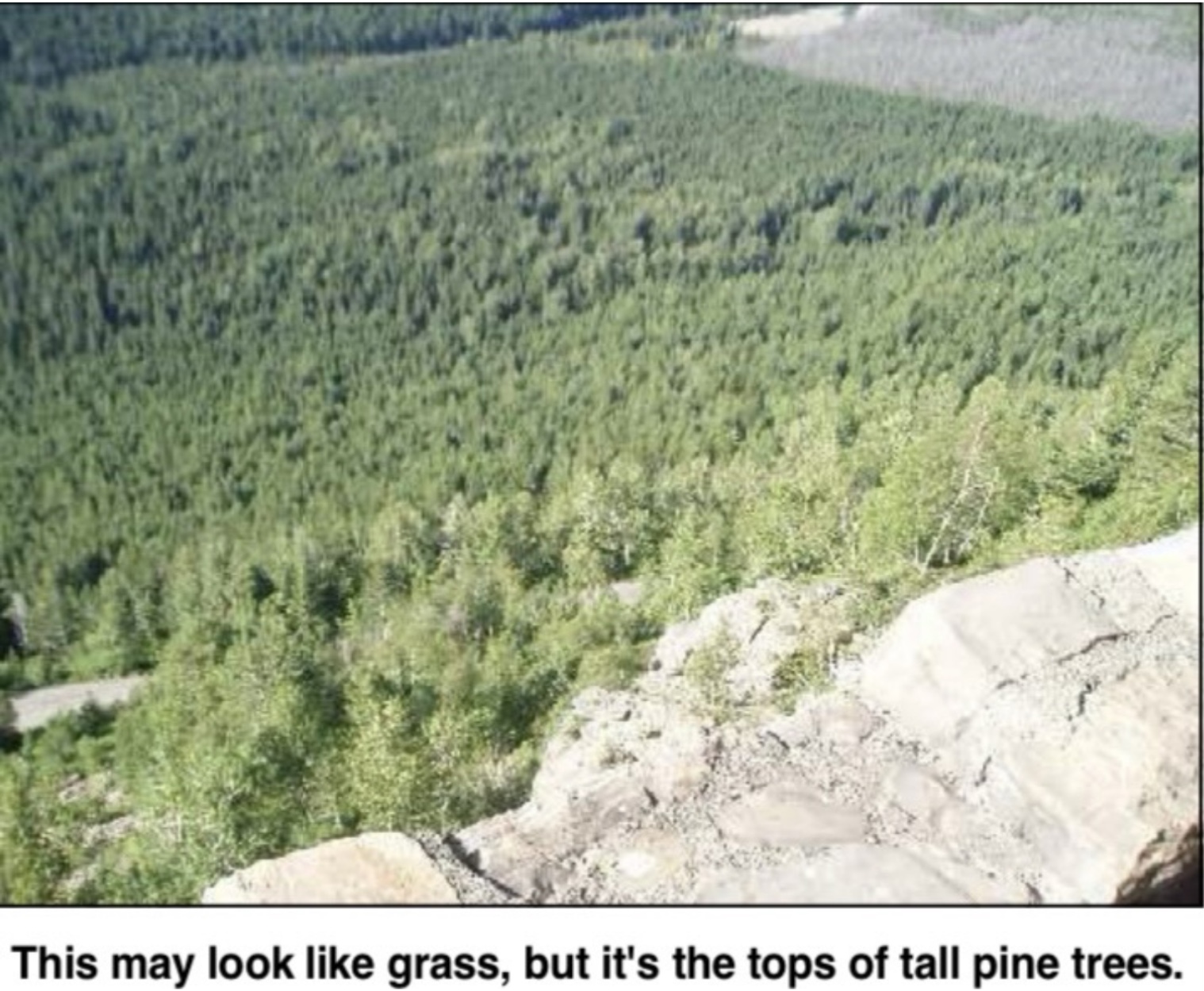

It is cliche to say that it looked like the view from an airplane, but like many cliches, there is an element of truth.

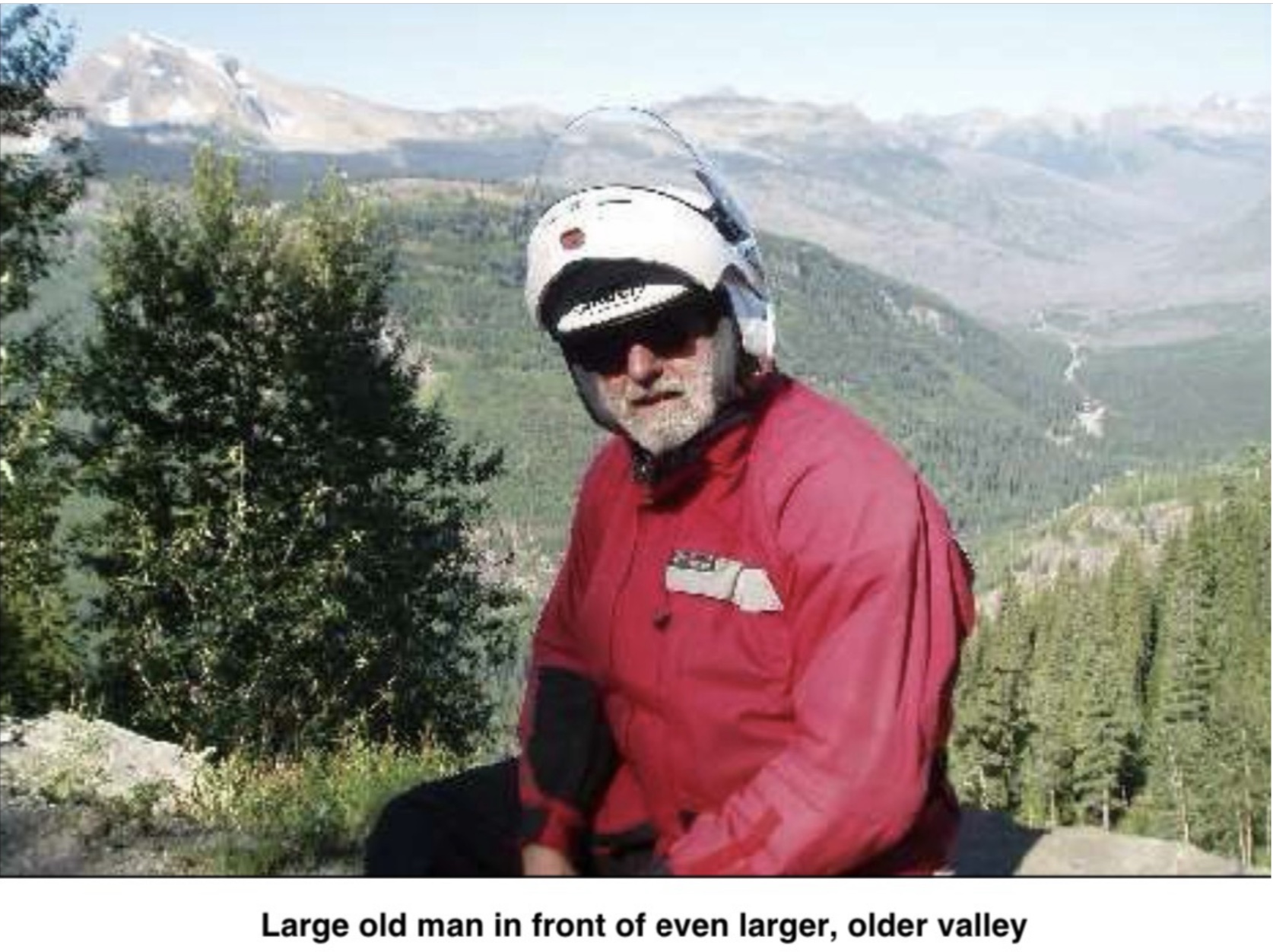

As we neared the top, nearly 7,000 feet up, the valley below spread out in a wide complicated series of U-shaped glacial excavations, so wide as to be almost impossible to take in at one view. These were “hanging valleys” where intersecting glaciers had cut off the path of the smaller ones, leaving a huge saddle leading to a drop-off of hundreds or thousands of feet… At the summit, we stopped for a break at the rest area and could see the bare rock peaks still towering above us. Along their sides was the effluvia of erosion, the flaking off of ever-smaller pieces flowing down like melting candle wax. Come back here in 10 million years and this summit will be down in the filled in valley….if another continental plate collision hasn’t started the process all over again.

On the other side of the summit pass, the road was gentler in its slope and the drop-off not quite so intimidating. We could feel the temperature rise as we descended until by the time we stopped for lunch at Kiowa we had to come out of our layers and switch to the ventilated gear. At the table, we spread out the map and contemplated our next move. The plan had been to go on down to Beartooth Pass and Yellowstone, but, using the new-found electronic mapping skills I had learned from Dave, we determined that such a route would have us over 1,000 miles from DuPont on or about Thursday, necessitating a burn across the high desert to get home, possibly involving the dreaded interstate travel. We decided to change course and head back into Idaho and over into Oregon to explore some mountain roads.

We went on south, along Route 83, eventually heading toward Seeley Lake. By this time, I had developed a killer head and chest cold, no doubt the gift of some generous passenger on my flight out. (Sharing the beer sampler in Whitefish included more than we thought. In another day, both of us had a serious cold, one which put a new cast on the trip. It is difficult to concentrate on riding when the wind through the faceshield is spreading nose drippings across one’s face.)

We stopped at a drugstore for various remedies and were soundly warned about watching for deer on the road to Seeley. We did see Bambi and his cousins several times on the route, but thanks to our heightened vigilance, neither deer nor BMW were harmed.

We found the last rooms at the small motel in Seeley Lake, operated by a young man who was from Harlan and at least claimed to know my daughter-in-law’s family.

Dinner was at the Dairy Queen wannabe a few yards down the road., brought back to the picnic table outside our room and washed down with a local Montana wine sourced from the combination Conoco gas station- Ace Hardware-and-wine store a short distance away. What red wine goes best with a crescent wrench, burger and fries?

From Seeley Lake, we headed southwest on Rt. 200, yet another mountain road, down to Missoula for breakfast. Thoroughly filled, we started up into the Lolo Pass area which had been recommended as a road not to be missed, surely something to produce lasting memories. It did, but not entirely of the kind we wanted. We both got “performance awards “ from the Idaho State Police.

We were on route 12 out of Missoula, up over the phenomenal Lolo Pass, enjoying the curves at the Montana speed limit of 70mph. It is a lovely mountain road, with wide sweepers following the iconic rocky stream, with the occasional set of switchbacks for added flavor. Jay said “That is the road I have been looking for all my life”.

The speed limit changes at the Idaho border from 70 mph to 55, a switch that I apparently didn’t take seriously enough. We came up behind a black SUV, sort of the standard vehicle in this part of the country and as I swung out to pass it, I noticed the state police logo on the side. He said it didn’t matter, he had clocked us both coming up behind him at 65 and was reaching for the light switch before I came up beside him. The trooper was polite, efficiently businesslike, and utterly without a sense of humor under the circumstances.

From that point forward we were forced to obey the limit carefully, which changed a formerly very enjoyable bike road into drudgery…. beautiful, scenic drudgery, but a chore nonetheless. These were curves that would accommodate a fully loaded school bus at 65mph, much less a motorcycle, and we were forced to hold it down to 50.

Not far from the site of our lawbreaking, we pulled into a layby and were quickly joined by a very animated young man on a bicycle.

He was, by his own account, an “Iron Butt” motorcyclist and gave us great detail on how he had prepped his bike, a Concours, for the long hours in the saddle (extra gas tank, various electronics, etc) and himself (a “Stadium Pal” relief device which would, I think, discourage tailgating.) He said that 1000-mile days on a motorcycle weren’t challenging (or masochistic) enough, so he had decided to ride a bicycle 5,000 miles cross country, corner to corner.

He told us about a road called “Whitebird Hill Road” out of the nearby town of Grangeville which had been the old way across the mountain before the new road bypassed it. We took his advice and found one of the best riding experiences of a trip already filled with such. Whitebird Hill Road was empty of vehicles (including those with official logos) and didn’t have a straight stretch more than 50 yards long for about 20 miles. Jay was on the Mystic, and I was doing my best to keep him in sight. The best part was that with the twistiness of the road, neither of us was breaking the speed limit of 55 mph while testing the limits of the tires and our nerves (not always the same limit). The road eventually connected to Rt. 95 right at the top of the Hells’s Canyon entrance where 95 began its descent in a long series of sweepers along the rim of an enormous valley.

For lodging that evening we found a small motel/B&B in New Meadows, Idaho, operated by a charming woman named JoBeth Mehen and her husband Steve, a plant scientist who had, she said, done some consulting work at our alma mater, University of Kentucky. The motel part was in two blocks of rooms arranged around a courtyard behind the large 4-square, end-of-the-19th century house. Inside the house was the motel office and a bar in what had been the front parlor. Her husband had constructed it from a single piece of wood, about eight feet long, three feet wide and at least 4 inches thick. He had embedded in the bar geographic markers from the highest summits around. There were tap handles for draft beer and a cooler case behind the bar with some interesting local brews. Jay and I thought that a full bar in the front parlor seemed like an excellent decorating idea, but on further reflection realized that, in our households, this may be a minority opinion.

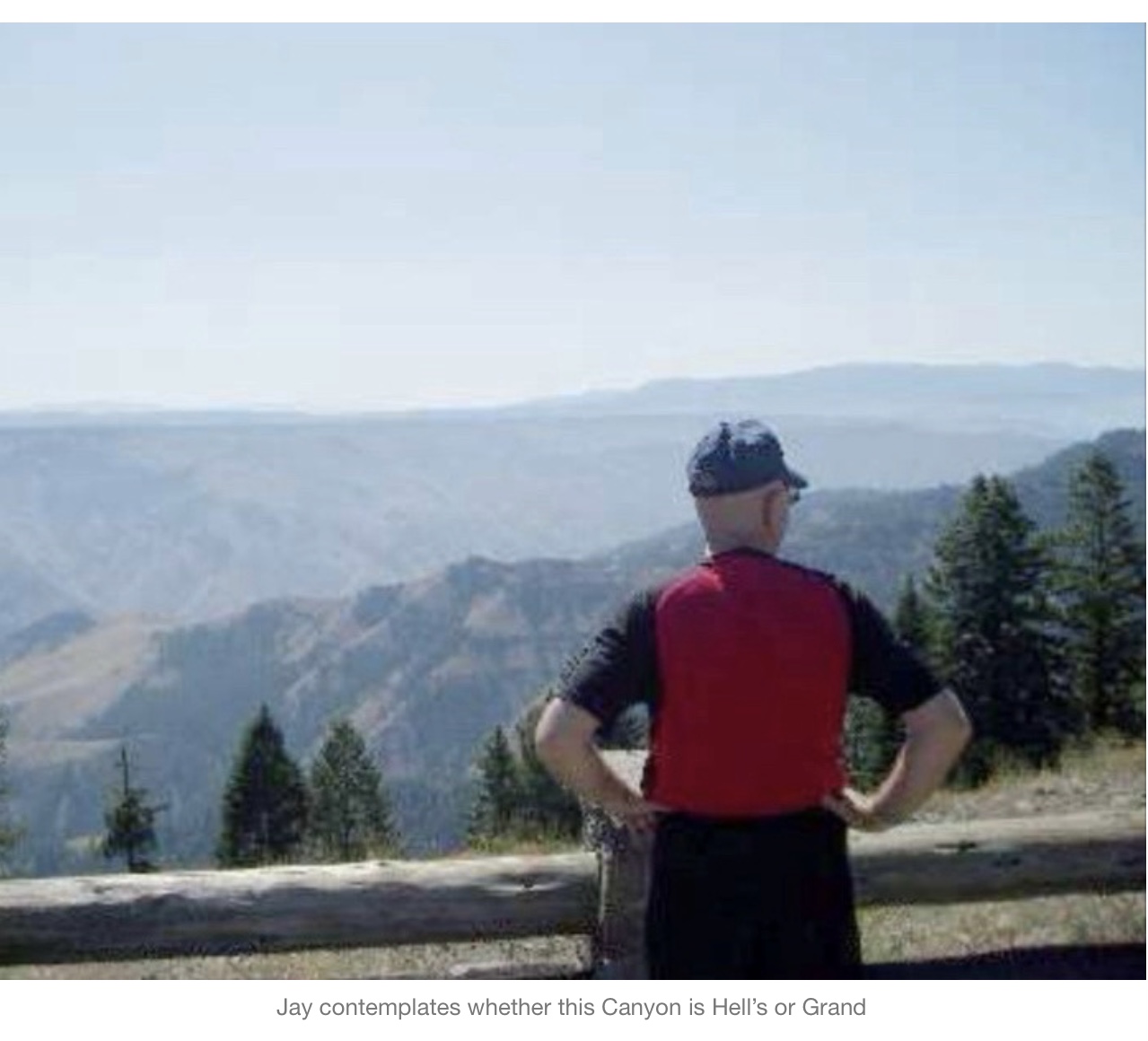

The next morning, we went into the Hells Canyon Park and crossed over into Oregon at the Browning Dam. From there we found the road up to the overlook where we could see across the 10-mile-wide canyon, which is one and a half miles deep. The sign at the overlook says this is the “largest gorge in North America” which is either a case of semantics or an argument for them to sort out with the Grand Canyon folks. One way or the other, it is big.

We were advised by some riders we met up there to take the unmarked road from the Canyon access over to 82 and into Joseph, Oregon. This turned out to be a marvelous road, skirting around the edges of Pete’s Point (elevation 9,700 feet) and down into a picturesque town spread out in the valley, again like in a classic western movie. No gunfights on the main street, though, just tourist stores and excellent restaurants for weary travelers. We ate lunch on the deck of a local brewpub and coffee house (no beer for us on a riding day).

Saddling up (though not quite as dramatic as in the westerns) we continued west on 82 down to LaGrand and then to North Powder (don’t these just sound like Shane and Rooster Cogburn must live there?) where we took off on a “white road” (unmarked and un-named roads on the Oregon map) across the Wallowa and Whitman National Forests and into the Anthony Lakes Ski area. The lodge was abandoned at this time of year, and that was the only sign of “civilization” we saw for nearly 100 miles.

Riding across the top of the pass, just over 7,000 feet, we could see in the far distance a huge column of smoke rising from the horizon, resembling those iconic photos you have seen of the mushroom cloud from a nuclear explosion. We later learned it was a massive forest fire in the Columbia River Basin, a couple hundred miles from us, but we briefly contemplated our options if while we were up here, “they’d dropped the Big One” ending it all. Our conclusion was, if so, then the heck with the speed limit! But, figuring that wasn’t the most likely explanation for what we saw, we proceeded on our law-abiding way.

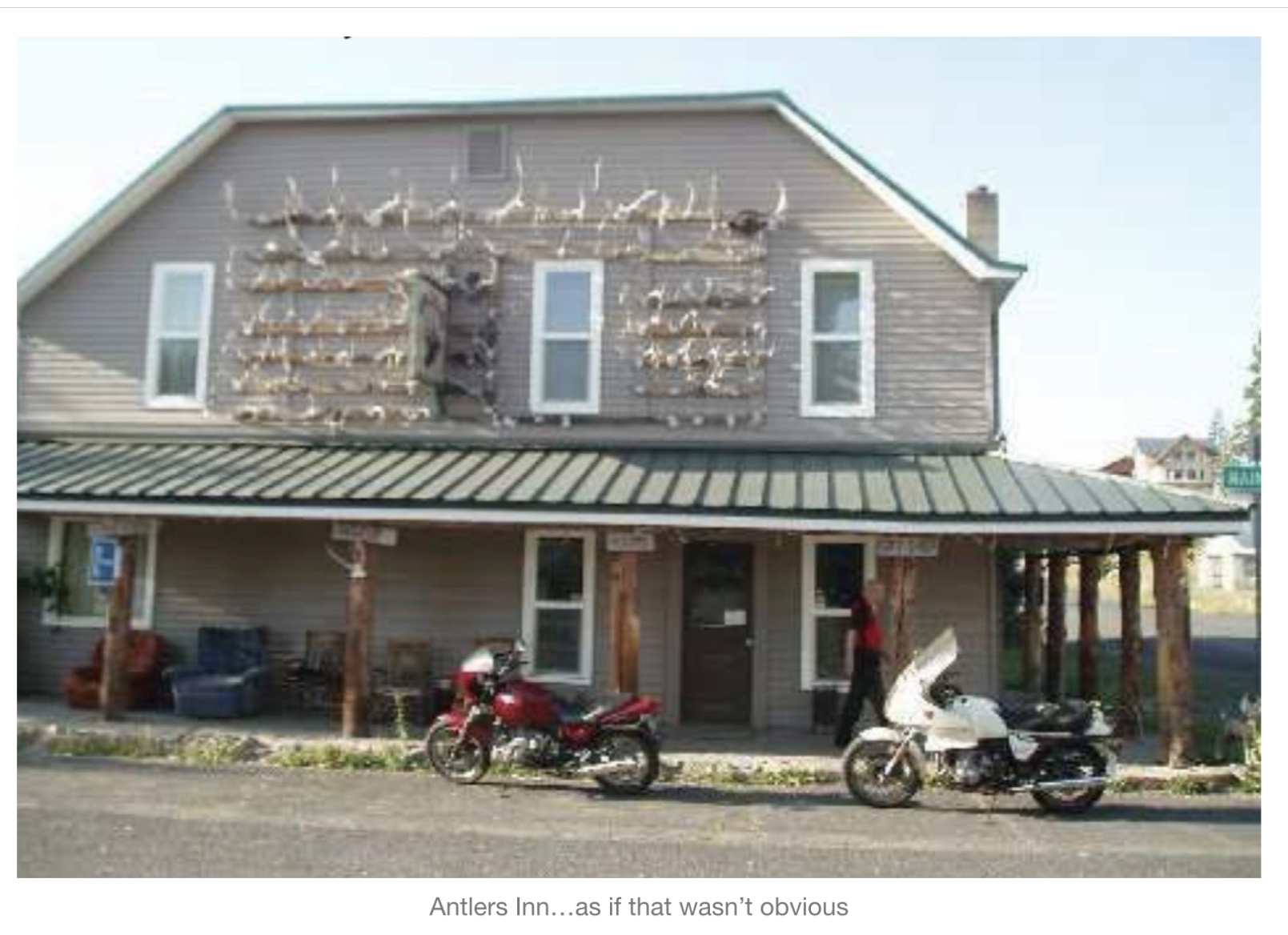

Our berth for the night turned out to be the Antlers Inn in Ukiah, Oregon, a town of about 300 souls. The only other choice was an RV park with “cabins” consisting of four wooden walls and bunk beds, facilities outside. The Antlers was a wooden two-story structure, festooned on the outside (and inside) with horns of various creatures screwed to the walls.

It appears to have been constructed in the 19th century, I think, as a rooming house for miners and loggers with a minimum of fuss and attention to comforts. The rooms were all on the second floor, small, hardly large enough for two beds, requiring that some of our gear be stowed on the bed as there wasn’t room on the floor to walk around it

The bathroom facilities were at the end of the hall, shared with the other guests, who were on this occasion government bat census workers who didn’t come in from their labors until about 3am. The “lobby” was small, maybe 8 x 10 with a secured window for check in and again, more antlers. Our check-in clerk was also the waitress at the bar nearby, the only eating establishment in town. We walked down there and took our seats at one of the bar tables and were given our choice of entrees…. a burger or a burger & fries. The beer selection leaned heavily toward made in St. Louis, but there were a few local brews, enough to get us through dinner satisfactorily. We listened with rapt attention while the waitress described in great detail to some of the regulars how much better things were now that she had gotten her new teeth.

From Ukiah we took another white road over to Heppner, going across Black Mountain (a mere 5,900 feet up) following Willow Creek to its reservoir. The mountains here are smoothly rounded, farther along in the erosion process, and shaded in various hues from the brown side of the crayon box. This is what that “Burnt Sienna” was made to color. Vegetation is low, scrub trees and bushes, just enough to provide shelter and food for some very hardy critters who live here. Along the banks of Willow Creek there are trees, looking almost like a planted lane for a park, but really just reflecting that this is the only place where there is enough water for anything more than a few feet high.

The town of Heppner is arranged along the valley floor, like all the others, and is supported by the vacationers who come for boating at the reservoir. Apparently, that recreational paradigm does not include breakfast, for there was no establishment serving such and the young attendant at the gas station gave me a quizzical look when I inquired, as if she had never given that option any prior consideration.

Up the valley road another 20 miles was the town of Ione (yes, another one) with one restaurant. There the waitress informed us that she liked cooking pancakes, but sometimes got “carried away” on the size. We accepted the challenge and were rewarded with wonderful hotcakes that overflowed the large plates meant to contain them. It took a while, but we managed to get most of them eaten while perusing the map to figure out where we were going from here.

Folks at the café gave us directions to another white road (“just past the school” ….as if we, first time here, would know where that was) which turned out to be exactly what we wanted. The rough pavement wound around some low hills then climbed quickly to a plateau. As we topped the rise, suddenly there was nothing but golden grass in ocean-like waves spread out before us as far as we could see in any direction, broken only by the thin black ribbon snaking off into nothing out in front. I tried to picture what it would have been like to be on horseback, before this road existed, coming upon such a sight. A horseman would have known that he could ride in any direction for days and it would still look just the same.

We had just a bit more traveling capacity, so before too long we were back on a “real” (i.e. marked) road toward Condon and then Fossil, through the John Day Fossil beds. These canyon roads are laid out along the erosion paths of the high desert, formed when the volcanic activity and sediment filled in the ancestral mountain valleys, then millions of years of rain and wind tried to take it all back. Layer upon layer of earth is exposed, along with the various fossils, etc. contained therein, like a written timeline if only one has the information to understand it. For the motorcyclist, however, the interpretation is much simpler. Water eroding earth makes some really interesting curves.

At Antelope we stopped for a pie break (well, actually “marionberry cobbler” to be precise) at the only commercial establishment in town.

On the wall were newspaper stories about a religious leader from India who had created a ranch nearby, with a fabulous mansion, then started bussing in homeless people from around the state to dominate local elections in a “takeover” attempt. The coup failed, the leader was exiled, leaving the mansion and ranch in the hands of a single caretaker (who had answered a “help wanted” ad without knowing what he would be caretaking) for years until another religious-based organization bought it for presumably less nefarious purposes.

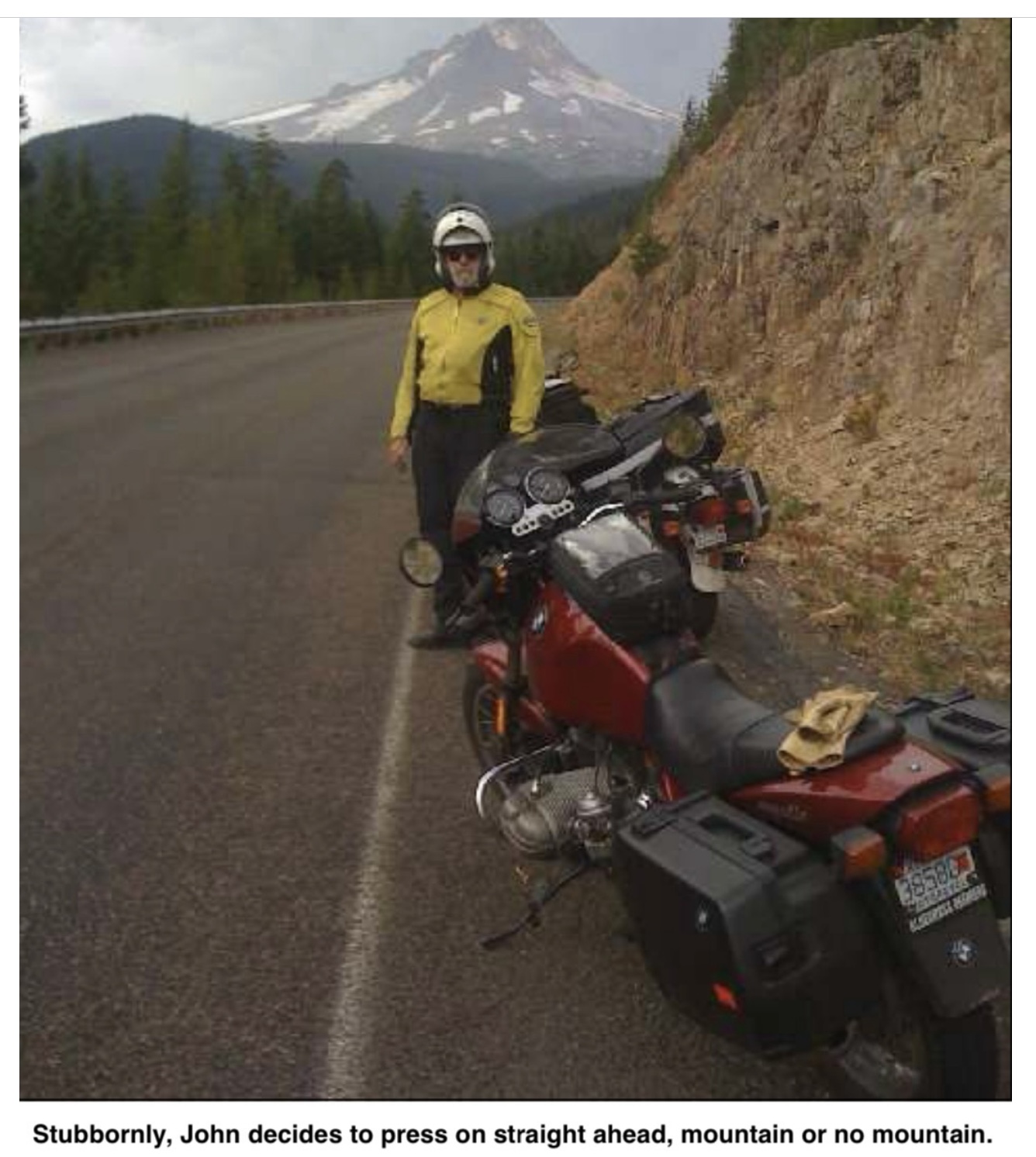

We found another white road coming out of Maupin, Oregon into the Tygh Valley, that purported to be the Barlow Trail, part of the Lewis & Clark route. It wiggled its way around the base of Mount Hood which would appear suddenly around a turn, standing enormous, snow on its flanks, then disappear again like some supernatural thing popping in and out of existence at will. At each appearance, the temperature would drop immediately, as the cold air from the mountain blew through the opening like heaven’s own air-conditioning vent.

We were alone up there on the Barlow Trail, with the traffic all gravitating to Route 35, the main thoroughfare into Hood River. Eventually we had to join them, heading down (a 26 mile constantly downhill run) to the town where we would spend the night.

Hood River is an excellent motorcycling destination town. It is small enough to be manageable but big enough and “touristy” enough to have all the interesting amenities, we found a room at a decent motel about three blocks from downtown and walked over to explore the restaurant situation. This was a Friday night, and the sidewalks were full of people on their way to and from apparently interesting amusements. One group of young folks was wearing masks and/or headgear, bobbing and weaving down the sidewalk to music only they could hear. I suspected chemical enhancement. We selected a place with a huge deck that afforded an excellent view of the river and the downtown frivolity. Over the next couple of hours, the beer selection was sampled, wonderful meals consumed and musings on the general state of the world (and how it would be better if everyone just agreed with us) were mused.

Breakfast the next morning was at the place just down the block from our motel, which specialized in the first meal of the day, and we benefited greatly from their expertise. Never let it be said that the possibilities of the egg have been exhausted!

We were on the downhill run now, always an awkward part of any trip. The end is in sight, but no one wants it to be over, so we must milk the last bits for all they are worth. We decided to go down the Columbia River on the Washington side to Portland, then head across the hills to the coast, crossing the river at the large bridge at Astoria. Following the Columbia, while not a technically challenging road, holds one’s interest because of the sheer enormity of it. They do things big here in the West and this river is a good example. Despite its size, there is surprisingly little commercial development for long stretches, probably because of the mountainous terrain that goes right down to the water, save for this thin band of asphalt.

Getting through Portland is something that just has to be endured, not enjoyed. Finally, we reached route 26 which took us away from the urban tangle and off again into the hills. After veering off onto the smaller Rt. 47, we stopped in the small village of Veronia for the morning pastry replenishment, at a Greek bakery. The Mediterranean coffee and baklava were so good that I tried two more of the delicately flavored offerings, even though I could not identify them. They were light, flaky and quite tasty which is all I needed to know.

Not long after Veronia, we took yet another branch road, 202, that promised to go off into the hills away from towns. We were not the only ones who had thought this road would be deserted. There was a curious sort of runner’s event going on. For several miles we saw individual runners, wearing numbers, trudging along the left side of the road. Some were running like the wind; some were plodding, and some were not much more than walking. One young woman was running, quite well actually, wearing what appeared to be a red cocktail dress. Ages ranged from teens to folks who looked even older than us. Every few miles there was a station with crowds of people checking in runners, milling about and generally looking like the end of a race…. but it wasn’t. Some runners stopped and then left those stations, some ran right on through. This continued for about 20 or more miles, with the road also clogged by minivans, each with the number of a runner, proceeding slowly along the route. Some of the runners we saw many miles from the start didn’t seem to be the sort that would have beaten all competitors to that point, so we surmised they must have started at one of the stations in the middle. We still have no idea what was happening.

We left the runners behind and found our way into the Astoria area to cross the mouth of the Columbia on the high, long bridge over to Washington. I have still not quite recovered from my trip across the Mackinaw Bridge back in 1988, so I was quite pleased to see that this structure didn’t have a metal grate bottom and the rails on the side went all the way to the road surface, not leaving a motorcycle-and- rider sized gap as on the Mackinaw.

On the Washington side we picked up 101 which would lead us along the coast. I had expected this area to be touristy, but the target market was not luxury cars with well-heeled sightseers, but SUVs towing boats, seriously seeking fish. It was starting to get late, so we were looking for a potential berth for the night, but accommodation seemed to be more fish camps than motels. At South Bend, we found a small motel, but the young clerk informed us that she had no rooms with more than one bed.

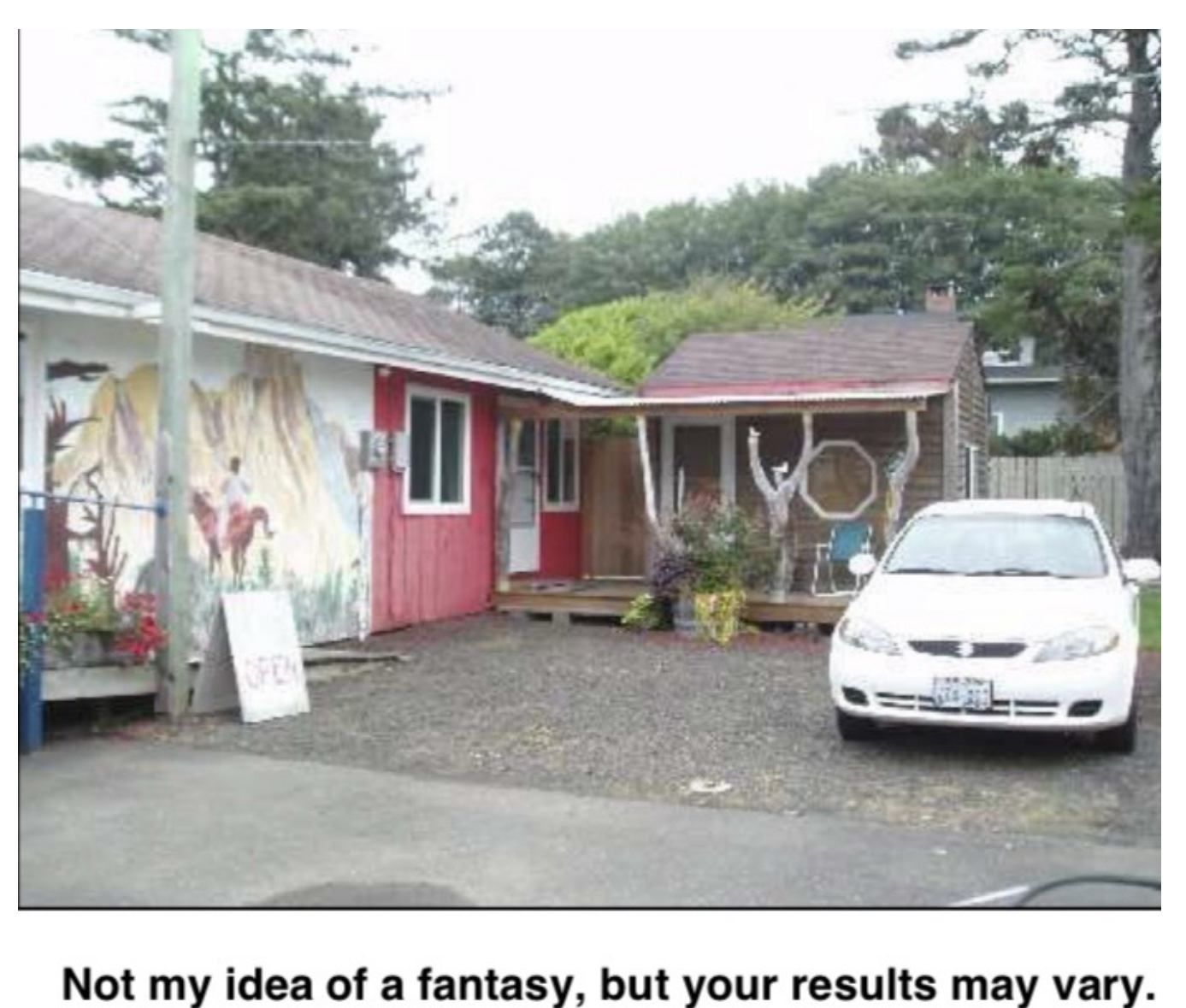

Relying on my newfound iPhone skills, (thanks Dave!) I looked up what might be available in the next town up. I called the first number and was told by the woman who answered that it wasn’t a motel. Then her voice dropped to a husky whisper, and she said “We have cabins (long, breathy pause) …. fantasy cabins…. (another drop in tone) …..for adults only”. I explained that my brother-in-law and I weren’t exactly in the market for such an experience and tried the next number. It was a Chinese restaurant which had a motel associated with it and that sounded great, if not actually a fantasy fulfillment. Chen’s motel did turn out to be quite acceptable for the evening, located on the highway, just across a field from the coastal waterfront. Breakfast was included in the price, providing us the next morning with what the menu described as “Happy Pancakes” ….and, actually, they were.

Our morning path took us through the town where the “fantasy cabins” were located. Despite the mental image that the overwrought clerk’s description might have engendered, they turned out to be very small wooden structures with rather amateurish paintings on the sides depicting such scenes as a knight in shabby armor on his way to rescue a somewhat bored looking damsel from some unspecified distress. Not sure how they would get the horse, much less the armored knight in that small cabin, but I will leave that to the intended participants.

The highway along the coast is usually separated by residences and fields enough to hide the ocean for much of its run up the southern portion. On the inland side, we saw several areas where it appeared that large swaths of trees had been felled, but not by saw or even bulldozed. It looked as if something, storm or similar force, had jumbled the trunks, roots and all, like an enormous tree salad in a 20 acre bowl. One of these had a sign sprouting incongruously from the middle that announced an 18-hole golf course for sale. I looked to see if there was fine print at the bottom saying, “some assembly required.”

Jay had been this way earlier in the summer and wanted to show me a beach he had found. On the rocky surface of this beach were logs easily twice the size of the trees we’d passed. The woods here have been clear cut numerous times (as announced by signs in front of the woods along the road) but these logs demonstrated what the old trees must have been like. Since riding motorcycles does tend to make one forget, at least for a while, how old one actually happens to be, I had to climb up on the log and walk its length.

At the root end, there was a sort of saddle in the wood which seemed like a perfect place for me to sit for a moment. As in many aspects of politics, war and life in general, one should never lose sight of the need for an exit strategy. I lowered myself into the saddle and immediately realized that modern nylon riding clothes and age-polished driftwood have a friction coefficient somewhat less than grease on a doorknob.

I began to slide forward and nothing I grabbed was any help in slowing my progress. I had a few seconds to try to pick a better (not good) place to fall off the end into the pile of smaller logs below. Fortunately Jay did not have the camera at the ready when I ingloriously sprawled out on the woodpile upside down and backwards. The phrase “easy as falling off a log” now has a more personal meaning.

We had intended to deviate off our route to go out to the furthest northwestern point in Washington, but by the time we got to the turnoff, the fog had set in such that visibility was down to zero over the ocean. We headed east, to Port Angeles, with lunch on our mind. We picked a detour off 101 that went somewhat inland, avoiding most of the fog, looping in and out of the foothills with gentle curves lined by tall trees. We noticed signs informing us of the names of the creeks we passed over, including “Uptha Creek”, “Itsa Creek” and one of my favorites, (I am not making these up) Pschidt Creek. We did not have a paddle.

At Port Angeles, we wandered around the waterfront development for a bit before selecting a restaurant with a balcony overlooking the sea. Our young waitress seemed puzzled by the two oddly dressed old men in the midst of the after-church lunch crowd, but she kept her professionalism and didn’t ask any questions.

Our last meal-on-the-road behind us, we set out on 101 south toward home. This route is gorgeous, following the Sound through small villages and wonderful shady curves….but this was tempered by our knowledge that the trip was ending and we had to get to DuPont before dark. As we neared the city environs, traffic picked up in volume and slowed down in progress until within just a few miles of Jay’s apartment, we joined I-5 and were at a standstill. Creeping on the last miles, a last stop for gas, then suddenly the turnoff for the subdivision and it was over, just that quick.

We put our gear away, then went for the last meal out at my favorite place, Jakes Restaurant & Grille on the Sound, about 5 miles or so from the apartment. We sat out on the deck overlooking the water with the mountains on the opposite shore. New beers were tried, an excellent dinner eaten and then there was nothing to do but watch the sun go down over the peaks and head for home….and start thinking about the next trip.